IN the first of these specially commissioned articles on worms, leading specialist Dr Siobhan McAuliffe MVB DACVIM looks at the life cycle of the major players and offers us an understanding of how these parasites come to infect horses and the diseases that they can cause. In the next three articles which will run over five months, Dr McAuliffe will cover testing for equine parasites, anthelmintic (wormer) products for horses and in the final article will share the latest research findings on putting a worming control program in place.

Equine parasites can be divided in a very simplistic fashion into two groups, the ‘major’ players or those that are capable of causing significant disease and the ‘minor’ players, which rarely if ever cause disease and which in general are susceptible to most anthelmintics (wormers).

The major players are:

The minor players are:

Small strongyles

Infection occurs following ingestion of third stage larvae on pasture. Exsheathment of this stage occurs through contact with gastric fluids and the exsheathed larvae pass through the small intestine. Invasion of the wall of the colon and caecum then occurs. The larvae moult to fourth stage and return to the lumen where a final moult to L5 occurs in adulthood.

Infections acquired indoors are considered rare as the third stage larvae is found attached to vegetation. Severe cold slows down development of eggs or stops it altogether.

Extreme heat (400C) will kill eggs and L3 in days. In temperate climates such as that of Ireland, eggs and L3 can survive for 6-9 months on pasture. Infection is acquired as soon as animals start grazing and small strongyle eggs are shed from 6-14 weeks after infection.

Disease

The most significant disease caused by small strongyles is larval cyathostomiasis. This occurs when there is mass emergence of larvae from the wall of the caecum and colon leading to diarrhea and a severe protein losing enteropathy which can result in death in many cases. Larval cyathostomiasis is most commonly seen in younger horses (up to six years of age). Severe infestations with mass feeding by adults can also cause poor thrift and weight loss.

The stimuli for the mass exodus of larvae includes seasonal factors (disease is seen in late autumn and winter in the northern hemisphere, but late spring or early summer in the southern hemisphere). Another important stimulus is the synchronous death of the lumen dwelling adults. A frequent scenario is where diarrhoea and a rapid weight loss follow the recent administration of an adulticidal anthelmintic (that is a product that kills adults only but does not treat larval stages in the wall).

The diagnosis of larval cyathostomiasis is difficult as since it is caused by larval stages, these cannot be detected with a faecal egg count (FEC). An experienced clinician can use a combination of relevant case history, clinical signs and laboratory findings to come to a presumptive diagnosis and response to therapy is definitive in most cases. Ultrasonography can be used to detect thickening and oedema of the colon wall and this can then be used to monitor response to therapy.

Chronic subclinical disease can result in extensive damage to the wall of the colon and caecum resulting in long term malabsorption and these horses are frequently recognised as poor doers in later life.

Large strongyles

These were historically regarded as the most significant parasite of horses. They are also known as migratory strongyles. Similar to small strongyles, infection occurs following ingestion of L3 on grass. Exsheathment occurs in the small intestine with penetration into the wall of the large intestine and moulting to L4, migration on or in intima of arteries of large intestine followed by migration to the cranial mesenteric artery and moulting to pre-adult stages.

These then migrate to the large intestine and penetrate the wall to enter the lumen where development to adults is completed. Depending on the species (S.edentatus, S.equinus, S.vulgaris), larval migration can involve the mesenteric arteries, liver and sub-peritoneal tissue, pancreas and renal tissue. Because of such lengthy migration, prepatent periods are also long, varying from six-12 months.

Disease

Large strongyles have to date shown no resistance to anthelmintics and as such disease caused by these parasites is now considered to be rare. It can still occasionally be seen on premises with extremely poor anthelmintic plans. Two different clinical syndromes are seen, both of which are related to the parasites’ passage through arteries than an effect on the gut itself. Thickening of the arterial walls and clots within the arteries caused by the parasite could lead to signs of severe colic related to death of the portion of intestine supplied by the blood vessel affected and intermittent lameness caused by clotting within the distal portion of the aorta. The aorta would not be a normal path of migration for the parasite but on occasion aberrant migration could occur with parasites ending up where they should not!

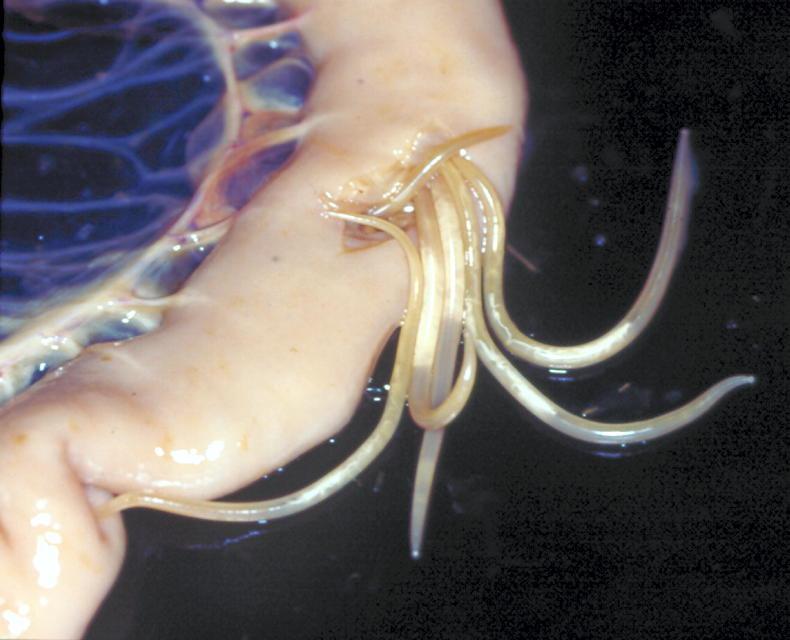

Also known as roundworms or a common lay term is “spaghetti” worms. The infective stage is the third stage larvae within the egg which can survive in the environment for several years and is unaffected by weather conditions. Unlike strongyles, contact with vegetation is not required and infections can be acquired within stables. This fact combined with the very resistant nature of the eggs means that large numbers of infective eggs can build up in the environment.

Following ingestion of eggs, release of L3 occurs in the stomach and small intestine, with subsequent penetration of intestinal veins. Somatic migration through the liver, heart and lungs then occurs. Larvae are then transferred to the respiratory system where they are transported by mucosal flow to the larynx and are swallowed and return to small intestine.

This process takes three weeks and another seven weeks of maturation is required before the first shedding of eggs. Adult females can shed hundreds of thousands of eggs but egg shedding is intermittent, making diagnosis through faecal egg counts difficult. If eggs are detected in the faeces of any animal in a group then the whole group should be treated.

Disease

Infestations are frequently sub-clinical. Clinical signs during migration are often related to lung lesions and include coughing and nasal discharge in young foals.

Bearing in mind that the time from ingestion to completion of migration is as short as three weeks and that infection can be acquired in the stall, it is not uncommon for respiratory signs associated with ascarid migration to be seen in very young foals. Heavy infections can lead to coughing, decreased weight gain and predispose to secondary infections. Ascarid impaction and intestinal rupture can also occur.

Larval stages cannot be diagnosed definitively and therefore disease based on larval migration is largely diagnosed based on clinical signs and response to therapy. Luminal stages can be detected by ultrasonography.

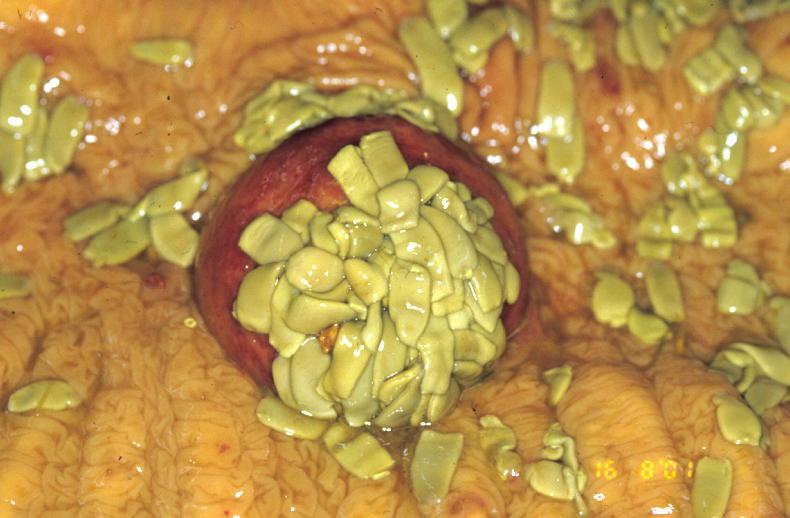

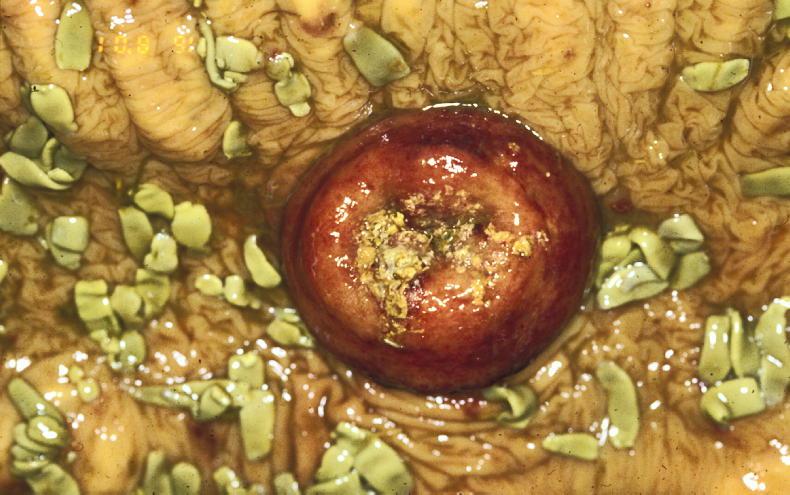

Two species of equine tapeworm are of significance in Europe: Anoplocephala perfoliate and Anoplocephala magna, although the latter is predominantly recognised in Spain. Infection occurs mainly during the second half of the grazing season and essentially only on pasture by ingesting infected intermediate hosts (orbatid mites).

The prepatent period is six weeks to four months. A.perfoliata adults inhabit caecum near ileocaecal junction and A.magna adults inhabit the small intestine. Higher prevalence of disease is seen in young horses less than two years of age.

Disease

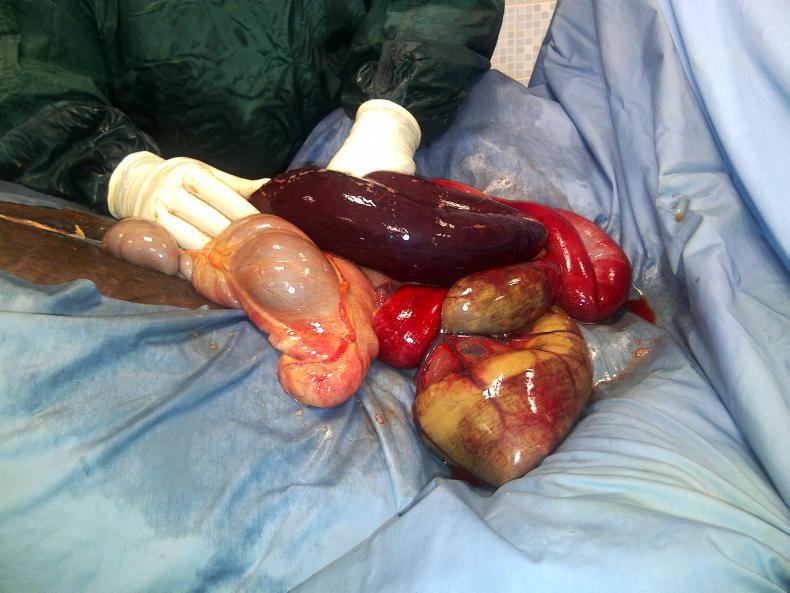

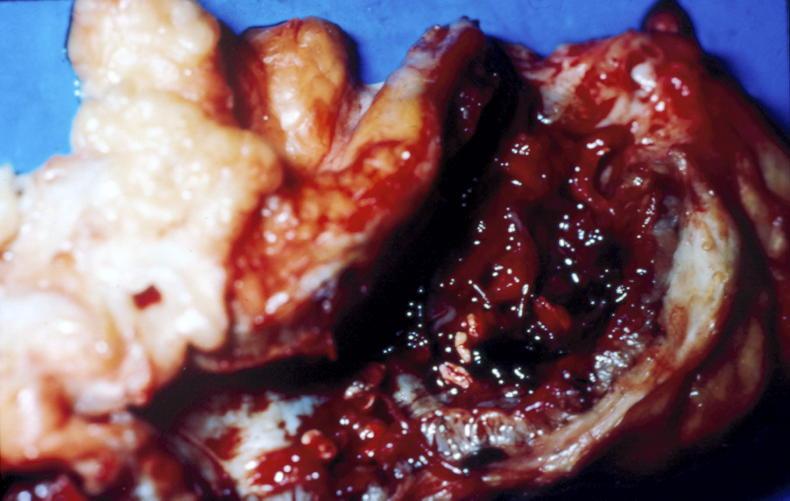

Higher infections can cause signs of colic associated with bowel irritation, ileal impactions, intussusceptions and intestinal obstruction.

These are most frequently seen in yearlings, but can be seen in weanlings or two-year-olds. The most common clinical profile is yearling that has a number of episodes of mild colic that resolve with little or no treatment followed by a more severe episode of colic related to a large intestinal intussusception (one section of intestine telescopes into another), requiring surgery.

Siobhan McAuliffe graduated from UCD in 1997. She worked in ambulatory equine practice in Ireland until 2001 when she took up a residency in Equine Internal Medicine at the then Hagyard, Davidson and McGee in Lexington, Kentucky. Following residency she took up a role at the Stables of King Abdullah in Saudi Arabia for five years. She then returned to Lexington for two years where she ran her own practice. In 2010, she took up a medicine position at the newly constructed Kawell Equine Hospital in Buenos Aires where she remained until returning to Ireland in 2017 to take up a medicine position at Fethard Equine Hospital. She now works as an internal medicine consultant in conjunction with a part-time pharmacovigilance role with MSD AH Ire. Siobhan has numerous publications in both English and Spanish.

Contact: mcauliffesiobhan@gmail.com

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

It looks like you're browsing in private mode

It looks like you're browsing in private mode

SHARING OPTIONS: