WITH all horse wormers becoming prescription-only medicines (POM) as of December 1st, expert advice on worming is now non-negotiable for us all. Dr Siobhan McAuliffe MBV DACVIM has shared a helpful case study for stud owners who face a problem with encysted red worm.

Case study problem description: Encysted redworm in yearlings and store horses

I have yearlings and store horses just not thriving or looking well. They’re well fed, they’ve been wormed since I bought them, but now three have died this year. The vet thinks I might have a problem with encysted redworms on my farm. How has this happened?

What have I done wrong? What do I need to do from now on to avoid this problem happening again? How does the vet know its an encysted redworm?

What may have gone wrong?

The problem likely developed because:

The wrong wormer was used or was administered at the wrong time of year.The dose may have been incorrect.Resistant parasites are present on the farm.Pasture management practices (such as spreading manure or mixing age groups) have increased exposure.Overstocking has led to high infection pressure.Diagnosis

The vet may suspect encysted redworm based on:

Clinical signs: rapid weight loss, diarrhoea, poor condition and group outbreaks.Blood tests: raised globulin levels and possibly a positive encysted red worm antibody test.History: recent worming with products not effective against encysted stages or no record of winter worming.

Causes and pathophysiology

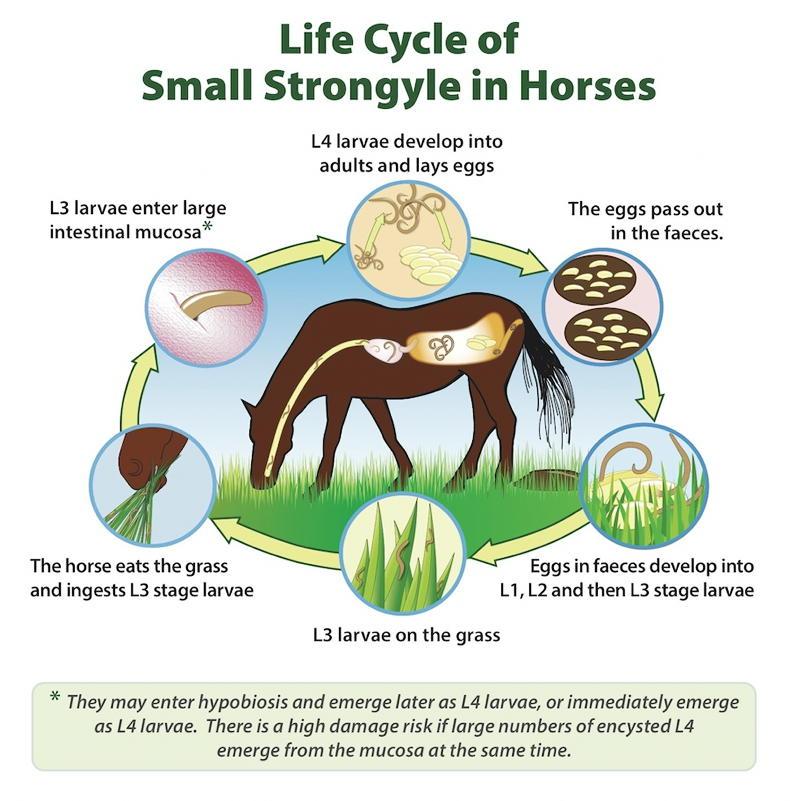

Encysted redworms are the larval stages of small strongyles (cyathostomes) that burrow into the lining of the large intestine and become dormant (encysted). When large numbers emerge suddenly - typically in late winter or early spring - they cause severe damage to the gut wall, resulting in inflammation, diarrhoea, weight loss and, in severe cases, death.

This problem may occur due to:

Use of wormers ineffective against encysted larvae.Resistance of redworms to certain wormers (especially benzimidazoles).Overstocking or poor pasture management, leading to high contamination levels.Incorrect dosing or timing of worming treatments.Mixing age groups, increasing exposure for younger horses.Environmental contamination of grazing areas with infective larvae.Treatment and control

1. Immediate treatment:

Use a wormer effective against encysted larvae, such as moxidectin or a five-day course of fenbendazole (Panacur Guard).Work with a vet to confirm which product is most appropriate.2. Testing and monitoring:

Carry out faecal egg count reduction tests to assess wormer effectiveness and detect resistance.Use regular faecal egg counts (FECs) to target future treatments.3.Pasture management:

Pick up droppings at least twice weekly.Avoid spreading manure directly onto grazing land.

Rotate and rest paddocks to reduce contamination.Co-graze with cattle or sheep to break the parasite’s life cycle.

4.Biosecurity:

Quarantine and worm all new arrivals before turnout.Keep new horses off main pastures for 48-72 hours after worming.5. Stocking density:

Reduce stocking rates where possible (ideally one horse per 1.5-2 acres).Prevention and future plan

Implement a strategic worming programme based on test results rather than routine dosing.Perform winter treatment for encysted redworm annually, ideally in late autumn using moxidectin (with vet guidance).Maintain detailed worming and testing records for all horses.Review and adapt management practices regularly with veterinary advice.Conclusion

The deaths and poor condition of the yearlings are likely due to encysted redworm infestation, either from resistant parasites or ineffective control practices. By combining effective worming, regular testing, and good pasture hygiene, future outbreaks can be prevented, and the health of young horses can be safeguarded going forward.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

It looks like you're browsing in private mode

It looks like you're browsing in private mode

SHARING OPTIONS: