FITTINGLY, it was when I was in Cheltenham last year that the thought first occurred to me that one way of looking at Ulysses is that it is a book about horses.

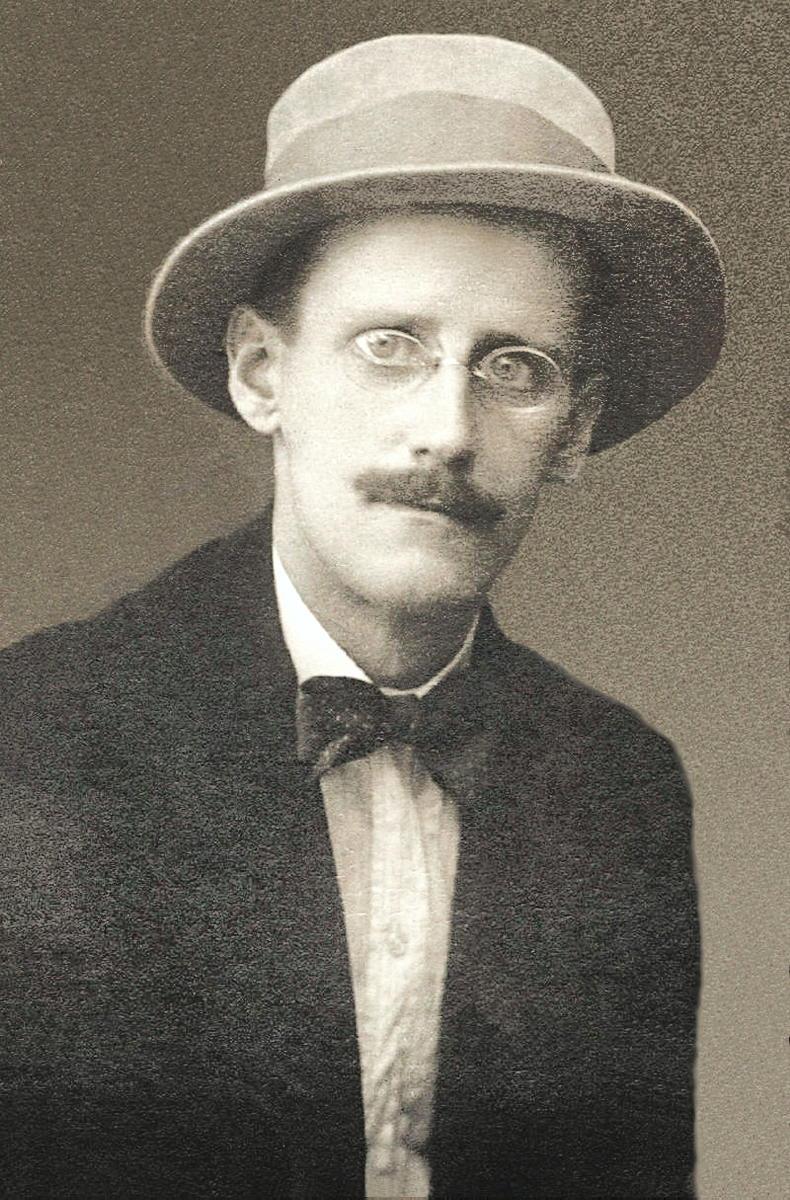

Although I maintain an interest in racing, developed from attending the races at Tramore in boyhood, I was not in Cheltenham for the horses, but to speak about James Joyce at that racing mecca’s annual literary festival.

It probably did not impress the locals when I revealed that the hallowed turf that features in Joyce’s novel is at Ascot rather than at Cheltenham. Let me explain about Joyce’s day at the races, and the role W.B. Yeats may have played as a tipster.

In the second episode of Ulysses, we are introduced to ‘images of vanished horses’ on the walls of Mr. Deasy’s office, “lord Hastings’ Repulse, the duke of Westminster’s Shotover, the duke of Beaufort’s Ceylon …”. Joyce’s famous novel is set on June 16th, 1904, the date of that year’s Ascot Gold Cup.

As we follow Joyce’s anti-hero, Leopold Bloom, around Dublin from breakfast time until the small hours of the following day, he is preoccupied all day with his wife, Molly, and her looming infidelity with Blazes Boylan, who we learn had made money from selling horses to the army for use in the Boer War.

Many of the novel’s other characters have their thoughts firmly fixed on that afternoon’s Gold Cup. In the ‘Lotus Eaters’ episode, Bantam Lyons asks Bloom if he can have a look at his copy of the Freeman’s Journal to check on the form for the race. Bloom, who is not a betting man, gives him the paper, which he says he was about to throw away.

Lyons immediately seizes on Bloom’s words and interprets them as a cryptic tip for Throwaway, one of the less fancied runners in the Gold Cup. Throwaway, trained by Herbert Braime and ridden by Willie Lane, went on to win at odds of 20/1. Lane had a hugely successful year in 1904, also winning the 1000 Guineas, the Oaks and the St. Leger.

Great dismay

The outsider’s Gold Cup triumph caused great dismay among the drinkers at Barney Kiernan’s pub that afternoon, as captured in the ‘Cyclops’ episode. Most had wagered on the favourites, Zinfandel and Sceptre. The belief that Bloom had made a killing on the race, and did not share his good fortune by standing a drink, contributes to the animosity he faces.

Lenehan, who had backed Sceptre, and who put Bantam Lyons off of backing Throwaway, comments that Bloom was ‘the only man in Dublin’ to back the outsider, ‘A dark horse.’

This misplaced hostility to Bloom ends with ‘the citizen’ hurling a biscuit tin at him as he flees the pub. In the, ’Eumaeus’ episode set in a cabman’s shelter near Butt Bridge, Bloom reads about the race in the evening paper, where he also sees himself misnamed as L. Boom among the also rans attending that morning’s funeral of Paddy Dignam at Glasnevin.

When Bloom returns to his home on Eccles Street, he comes across evidence of Boylan’s visit to Molly. He has the indignity of seeing evidence of Boylan’s presence around the house, including his imprint on the Blooms’ marriage bed and some flakes of potted meat that Boylan had evidently consumed there. Imagine that! Bloom must have taken some compensatory satisfaction from his discovery of two losing betting slips belonging to his nemesis. We learned earlier in the novel that Boylan had ‘plunged two quid’ on Sceptre for himself and ‘a lady friend’, Molly.

Yeats’ Galway

Yeats too sometimes dwelt on equestrian themes, including the Galway races:-

There where the course is,

Delight makes all of one mind,

The riders upon the galloping horses,

The crowd that closes in behind.

It may come as a surprise to many to learn that Yeats was well-informed about horses. The English writer, G.K. Chesterton, confessed himself to have been astonished by the poet’s expertise in that area. That knowledge probably came from his Sligo-based uncle, George Pollexfen, who was a renowned horseman as Yeats recorded in one of his poems.

And then I think of old George Pollexfen,

In muscular youth well known to Mayo men

For horsemanship at meets or at racecourses,

That could have shown how pure-bred horses

And solid men, for all their passion, live

But as the outrageous stars incline …. .

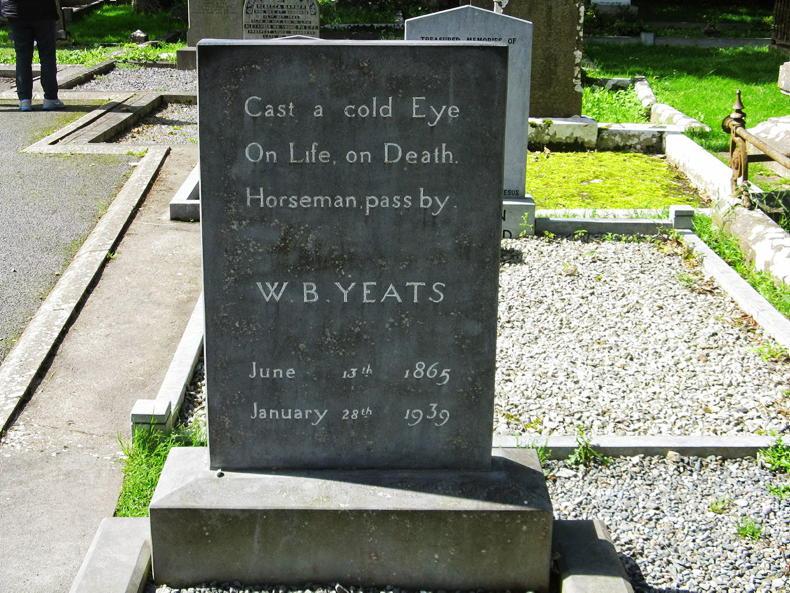

Later in his writing life, Yeats would extol the ‘hard riding country gentlemen’ of his imagination, while his famous epitaph urges a figurative horseman to “pass by” his grave at Drumcliff.

In the opening years of the 20th century, Yeats spoke out against the visit of Queen Victoria to Ireland in 1900, and wrote the robustly nationalistic play, Kathleen ni Houlihan, in which Maud Gonne played the lead role when it premiered in Dublin in April 1902. Then, in 1903, he signed a strongly-worded letter opposing the visit of King Edward VII.

Royal party

After the royal party had returned to London, Yeats wrote to Arthur Griffith’s paper, The United Irishman, about the monarch’s visit to Maynooth when, as he put it, ‘by a happy inspiration not to be expected from that quarter’, the College’s reception room was draped in ‘His Majesty’s racing colours’ and sported images of two of his horses, Ambush II and Diamond Jubilee.

With tongue firmly in cheek, he was glad to note that parishes hosting race meetings would henceforth be the most sought after by ambitious priests. Yeats laid a sarcastic ambush for Ireland’s two leading Catholic churchmen when he expressed the hope that Cardinal Logue will have ‘something’ on Sceptre and that Archbishop Walsh has ‘a little bit of all right’ for the Chester Cup.

Yeats relished this modicum of revenge for Cardinal Logue’s condemnation of his play, The Countess Cathleen, when it was performed in Dublin in 1899. He also suspected that the Catholic Church was behind the persistent attacks on him by D.P. Moran in his Irish weekly, The Leader.

Yes, Sceptre is the very same horse that let Boylan down in the 1904 Gold Cup. This makes me wonder if Joyce had read Yeats’s letter in the United Irishman, a publication he is known to have admired. That’s because the King’s visit to Maynooth features in almost identical terms in the ‘Cyclops’ episode.

Holy boys

There, Joe Hynes asks about ‘the holy boys, the priests and bishops of Ireland doing up his room in Maynooth in his Satanic Majesty’s racing colours and sticking up pictures of all the horses his jockeys rode.’ This leads to a ribald enquiry from Alf as to why Maynooth did not display images of the King’s women, to which, quick as a flash, J.J. responds that ‘considerations of space influenced their lordships’ decision.’

As it happens, Yeats was friendly with Lord Howard de Walden, a notable sailor, Olympic fencer, Jockey Club member and owner of the 1905 Ascot Gold Cup winner.

In that same year, Yeats was a weekend guest at Howard de Walden’s 17th century mansion, Audley End House in Essex. His host, who evidently had a qualified affection for him, once said that ‘one should never lose an opportunity of listening to Yeats though one should forget what he said’.

Even if Ulysses had been set in 1905 instead of 1904, Blazes Boylan would still have lost his bet, for Lord Howard de Walden was the owner of Zinfandel and not Sceptre. As Lenehan put it, after he had heard the Gold Cup result and ended up looking ‘like a fellow that lost a bob and found a tanner’, ‘Frailty, thy name is Sceptre’.

Yes, I think that Yeats probably did, like Leopold Bloom, unwittingly give a poet’s racing tip to that literary thoroughbred, James Joyce.

Daniel Mulhall is Parnell Fellow at Magdalene College, Cambridge and Honorary President of the Yeats Society. His latest book is Ulysses: A Reader’s Odyssey (New Island Books, 2022). He is a former Ambassador of Ireland to the United States, and has also been Ireland’s Ambassador to the United Kingdom, Germany and Malaysia

Twitter: @DanMulhall

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

It looks like you're browsing in private mode

It looks like you're browsing in private mode

SHARING OPTIONS: