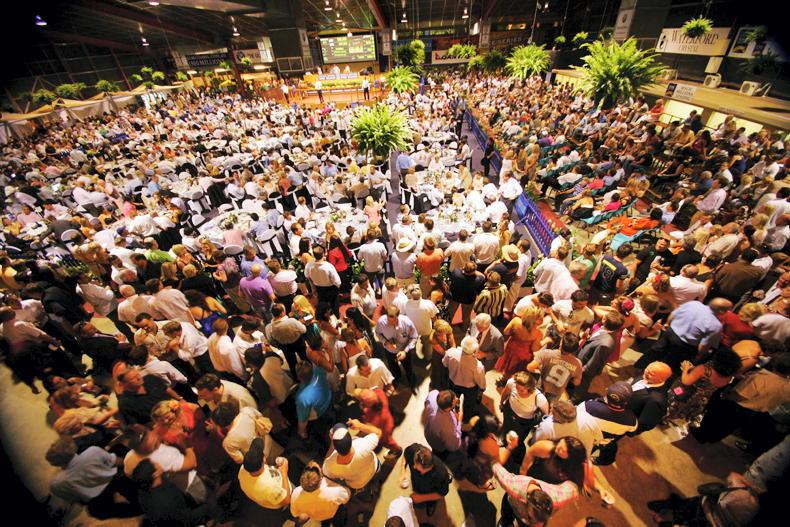

In 1986, cattle farmer Carl Waugh bought an empty slab of land just a stone’s throw from Queensland’s famous strip, Surfers Paradise, with a plan to establish a thoroughbred auction house that would shake racing to its core.

Magic Millions became a world-first concept. The idea was to boost the value of yearling prices with exclusive, wildly rich races. What could go wrong?

By 1990 it had all fallen apart. Magic Millions was in receivership and Waugh was gone from the building. Through seven long years, the company crashed and burned until business moguls Gerry Harvey, John Singleton and Rob Ferguson entered the picture.

Magic Millions, as is it known today, was born; a leading international sales and racing brand rich in sunshine, glamour, innovation and prize money.

In Magic Millions, award-winning author Jessica Owers has pieced together the spectacular, untold survival story of the Gold Coast company that is Magic Millions, from its controversial beginnings to its financial struggles through the 1990s and its eventual, dazzling success in the ownership of Harvey and wife Katie Page, right to the day it sold Winx as a A$230,000 baby.

Magic Millions is a gripping industry story, a riveting racing history and an untold Queensland fairytale. It’s the story of a company that almost didn’t make it but which became a powerhouse in the sensational, high-stakes world of international bloodstock.

JOHN Singleton was a Sydney ad man into whose face all the fire of life was crowded. Later, his biographer Gerald Stone would describe him as ‘an explosive genius on a lit fuse’, his eruptions professionally, emotionally and financially making headlines since the 1970s.

By 1997, he was a well-established millionaire, but unlike Gerry Harvey, Singleton lived like one. He drove a Rolls Royce, flew private, spared little and married often, his restlessness an expense only a rich man could afford.

The two men had first met in 1962. Singleton was barely 20 years old, Harvey two years his senior. Singleton was early in the advertising business, but he’d had it on good advice that a client like Harvey, the snappy white goods retailer out at Arncliffe, could be a tide turner.

He made up a brochure and carried it out to the Norman Ross store, by then open just months, and ran into Harvey at his withering best. The retailer stubbed out his cigarette on the shiny brochure and told Singleton he ‘didn’t give a fuck about advertising’. They were friends immediately.

Singleton stood well over six feet with a rugby player’s silhouette and the blondness of a Bondi surfer. He smiled broad, hiding nothing, and loved as loose as he lived; wives were beautiful and numerous and dazzled by him.

Professionally, Singleton was one of the top creative minds in Australian advertising. He’d had immense success creating ads that spoke to the common Australian, and the simpler and more common the better. He had dreamt up ads in taxis and on the telephone and when out on the beers, and he used everything from priests and housewives to sell for David Jones, Jaxx Tyres and even Kerry Packer.

An ABC programme in 1971 said he might be a ‘young tycoon of Australian advertising’ or ‘a racketeering pirate with downright questionable ethics’. Either way, John Singleton was a force, like water running uphill.

Advertising had made him rich and infamous, but Singleton had slid in and out of money his entire career, and, like Gerry Harvey, he lost a lot of it on horses. The two friends had paired up plenty in ownership because the clamour and pace of the racecourse suited Singleton.

He had been one of the key shareholders (alongside Ray Stehr) in the globetrotting Australian star Strawberry Road, but he had sold out when the horse was at his top. The ad man had done this many times in his life; he climbed the rigging right to the top of something, grew antsy and bored of the view and leaped off, his character drawn to reckless extremes. He had done it with women, horses, farms and businesses.

In April 1997, Singleton had just held a dispersal sale to heavily shed his bloodstock portfolio. It had been the result of one of those moments when he had thrown his hands in the air, ‘fuck it, sell ’em all’, and consigned the bulk of his stock to the sale ring. So when Gerry Harvey rang him to offer him a 25% share in Magic Millions, the conversation was brief.

‘You can’t be fucking serious? I’ve just sold all my fucking horses. No.’

It wasn’t the first time Singleton had turned down his old friend. Harvey had invited him into the retail game when he was establishing Harvey Norman but Singleton had declined, the opportunity to co-own category killer ‘Harvey Singleton’ just not appealing enough. Occasionally, he regretted the decision but waved it away with an assertion that a life selling fridges would have been tremendously dull.

In the minutes after hanging up the telephone on Harvey’s offer of Magic Millions, Singleton reconsidered long enough to think about his decision to reject it. At an overall asking price of $7 million, the Queensland auction house was going cheap because a quarter share, which Harvey was offering, was worth just $1.75 million.

Singleton was convinced that the money would come back to him in no time. Perhaps he remembered the folly of turning down Harvey all those years ago; his friend now had the kind of steady wealth he could only dream about. Not even 10 minutes had passed before Singleton picked up the telephone, reached Harvey and told him he was in.

Merchant banker

To Singleton’s swift and caustic character, 51-year-old Rob Ferguson was class and emphasis. He was the CEO of the merchant bank firm Bankers Trust Australia, or simply BT, a company he had joined in 1972.

BT had run amok in the banking establishment with its low-cost, anti-hidebound and revolutionary attitudes, but in a financial industry with egos like polar needles, Ferguson was considered and humane. Later, BT biographer Gideon Haigh would say that Ferguson had his ego ‘well under control, could see past, over and round it’.

Ferguson had a pensive expression under thick, dark brows and a long forehead. He was a thinker and mentor, championing the best out of people. He wasn’t brash or loud or compulsive, wearing instead an optimistic after-dinner mood, but there was no disguising his terrier-like instincts in the financial markets.

In the early 1970s, he had one day returned to the office from a meeting with construction company Mainline, adamant that BT shed all of its Mainline stock. ‘I’ve just been to see the CEO and the guy has no idea what he’s doing,’ he said. ‘We’ve got to sell the stock,’ and by 1974 Mainline collapsed.

Gideon Haigh observed Ferguson as ‘a retiring character with an eclecticism that took him far from investment banking’. Ferguson had travelled, owned a restaurant, and in 1989 had bought Torryburn Stud, a farm in the Paterson Valley with a heritage homestead once occupied by Australian poet Dorothea Mackellar. Under him and wife Jenny, Torryburn became a world-class boutique thoroughbred farm.

In April 1997, when Ferguson took a telephone call from Gerry Harvey about Magic Millions, he said yes to the partnership almost immediately.

It was almost unusual because nothing was impulsive with Rob Ferguson, as it rarely is with merchant banker types. He and Harvey had known each other a long time, as people in big business often do.

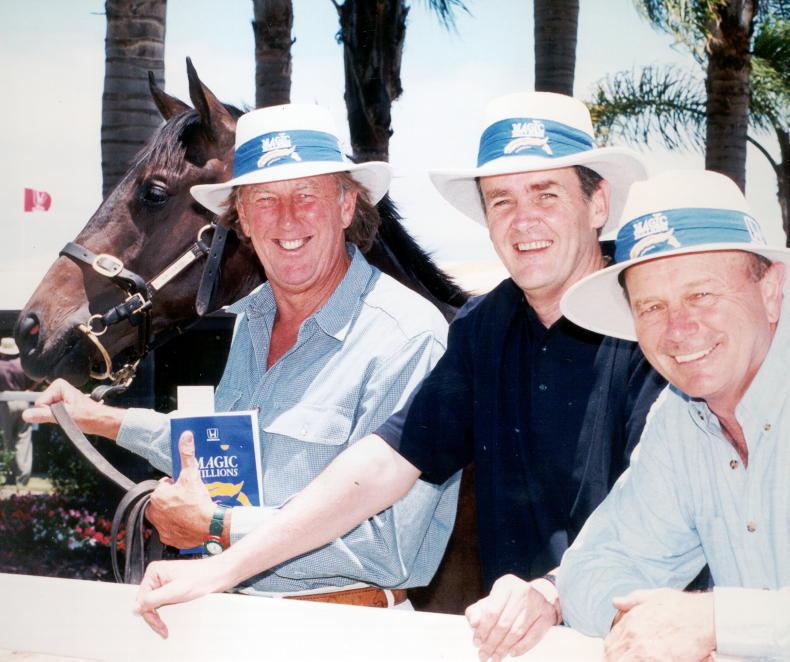

For Harvey, it was rare in his business life that the first two people he approached for partnership agreed to partner, but that is what happened when Gerry Harvey offered quarter shares in Magic Millions to John Singleton and Rob Ferguson. Harvey had to turn down trainer T.J. Smith just days later, the trainer enquiring of Harvey for a 50% share.

Of the two men who did buy in, they were very different. Singleton was a man who prompted rebellion, a type who would launch himself like Superman across a dining table of important people, while Ferguson was the kind more likely to be seated at the table. One carried the holiday in his eye all year round, the other a figure full of decision and dignity.

Harvey didn’t invite Ferguson in to cool Singleton’s jets, but that was inevitably how it seemed. They took control of Magic Millions on Friday, May 27th, 1997.

Going public

The first the public heard of it was through David Hickie’s ‘Gadfly’ column, which on Sunday, April 27th, a day after racing at Rosehill, revealed that ‘the biggest whisper at the ’Hill yesterday was that longtime racing buddies, ad man John Singleton and retailer Gerry Harvey, have paid an unconfirmed $7 million for the Magic Millions sales complex on the Gold Coast, lock, stock and barrel’.

Hickie could not raise a comment from either man to confirm the rumour, but, soon after, the Australian Financial Review picked up the scent, this time confirming Rob Ferguson was part of the picture. ‘All three love the thud of hoof on grass’, it declared, before the first public comment by Harvey on the sale. ‘We can do a lot with this company,’ he said. ‘All auction houses have the same audience. We just have to make this one more appealing.’

The new partners were spurred for the future of Magic Millions by the recent performance of the Easter Sale in Sydney. Buyers at Newmarket had coughed up the highest prices for year-lings since 1989, though the landscape of the market was totally different.

In 1989, there had been no Danehill and the stallion picture was local; in 1997, it was dominated by the progeny of shuttle stallions. Sadler’s Wells had virtually stolen the show with four yearlings averaging $380,000, and almost half of the stallions represented in the catalogue were Coolmore shuttlers.

But the bigger picture was that, despite a 3% stock market dive on the day the Easter Sale opened, the clearance rate was a healthy 87% for a $98,739 average. The median was up $20,000 on 1996, Reg Inglis visibly relieved.

Expansion plan

The outlook was finally good for the yearling industry and, if there was anything Gerry Harvey and Rob Ferguson were good at, it was watching market trends. Harvey wasn’t taking over Magic Millions to put William Inglis and Son out of business. Instead, he recognised that Magic Millions had a slice of the market and it was his opinion that that slice could be bigger. As he had done with Harvey Norman, expansion and numbers would be the name of the game on the Gold Coast.

At Ascot Court, the change of ownership had little immediate effect because Harvey, Singleton and Ferguson made no changes to the payroll. David Chester was Harvey’s man on the ground and remained the company’s bloodstock manager, and though Don Hancock had planned to exit the stage with Max Warner, Harvey asked him to remain as managing director for six months, to which Hancock agreed.

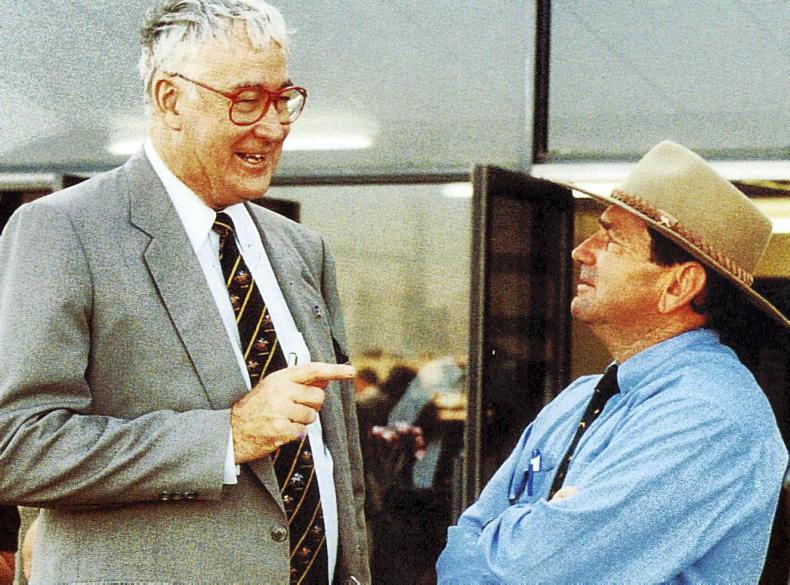

The energetic Max Donnelly, whose active role as Magic Millions receiver had ended with the buyout by General Accident, but who had lingered in the credit picture ever since, agreed to remain in the role remotely from Sydney under Harvey’s behest, which left just the maestro of the trio. Max Warner was finally able to close the file on Magic Millions, one of the last remaining active files he had in his folder of bad debts.

It had taken him five years to steer the ship off the rocks, and though glory was deserved, he had no appetite for it. He had closed bigger files than Magic Millions, but few cases, he admitted, had been more enjoyable than the Queensland auction house. There was something about the flow of money through bloodstock that had addictive appeal.

In later years, Warner’s role in saving Magic Millions would be overlooked in the dazzling hues of the new owners. His job from 1992 to 1997 had not been to turn the company into a Fortune 500 goldmine; it had been to put its head above water such that it could be sold to someone like Harvey. None but a man hard with conviction and resolve could have done it.

When the final papers were exchanged and Magic Millions was handed over, and Max Warner shifted his genius elsewhere with a wordless farewell, the last illusions of struggle disappeared from Ascot Court.

Magic Millions by Jessica Owers was released on October 21st, by Penguin Random House Australia.

ISBN: 978 1 76314 813 6

Available for international delivery from abbeys.com.au or from readings.com.au ($49.99)

Web: penguin.com.au/books/magic-millions-9781761348136 for further information

Web: jessicaowers.com

Jessica Owers is one of the strongest and most recognised female voices in Australian racing. Magic Millions is her third book. Her previous two books, Peter Pan and Shannon, were award-winning industry biographies.

Born in Ireland, Jessica is a graduate of the University of Stirling in Scotland. In 2023 she was a Kennedy Award finalist in the category of Racing Writer of the Year. She has lived in Cork and Edinburgh and now lives with her two children and Irish Setter in Sydney’s east.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

It looks like you're browsing in private mode

It looks like you're browsing in private mode

SHARING OPTIONS: